Macro Outlook: Monday Nov. 8 @ 12:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM GMT - GS Global Research Webcast: Global Macro Outlook1

Please join us on a live webcast for an update on the global macro outlook.

If you or any part of your organisation is subject to the research inducement rules of a member state of the European Union implementing the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive 2014/65/EU (MiFID II), please ensure that your organisation has entered into a separate agreement with GS for the payment of research services. If you have any questions, please contact your GS representative.

Goldman Sachs agrees to host this conference on the basis that no third-party speaker will provide confidential or material, non-public information. In addition, by attending this conference, you provide Goldman Sachs the right to record and re-distribute the conference information. The views of third party speakers do not necessarily reflect those of Goldman Sachs.

Disclosures applicable to research with respect to issuers, if any, mentioned herein are available through your Goldman Sachs representative or at http://www.gs.com/research/hedge.html. Please see http://www.gs.com/disclaimer/email/ for further information on confidentiality and the risks inherent in electronic communication.

[Enter section heading here]

In recent months, we have also become more optimistic about the impact of fiscal policy on growth. This is straightforward in the Euro area, where the likely German center-left coalition looks set to spend more and the EU Recovery Fund will start funding investment projects in greater size next year.[3] But even in the US, the outlook is better than suggested by standard measures of the fiscal impulse.[4] The fact that the US personal saving rate remains at 7.5% as of September—a month with strong consumption and mostly without extended unemployment benefits—suggests that consumers have already largely absorbed the loss of government support without either a meaningful cutback in spending or an undue decline in the saving rate. Moreover, it suggests that the consumption boost from the $2.4trn stock in US pent-up savings is still ahead of us, at least in aggregate. Combined with the passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill on November 5—which we had assumed but which had been held up in intra-party Democratic wrangling—this has made us less concerned about a large negative US fiscal impulse than we were a few months ago.

Growth trends in the major emerging economies are likely to look more disparate, with relative weakness—both relative to consensus and to the long-term trend—in China and Brazil, but strong performance in India and Russia.

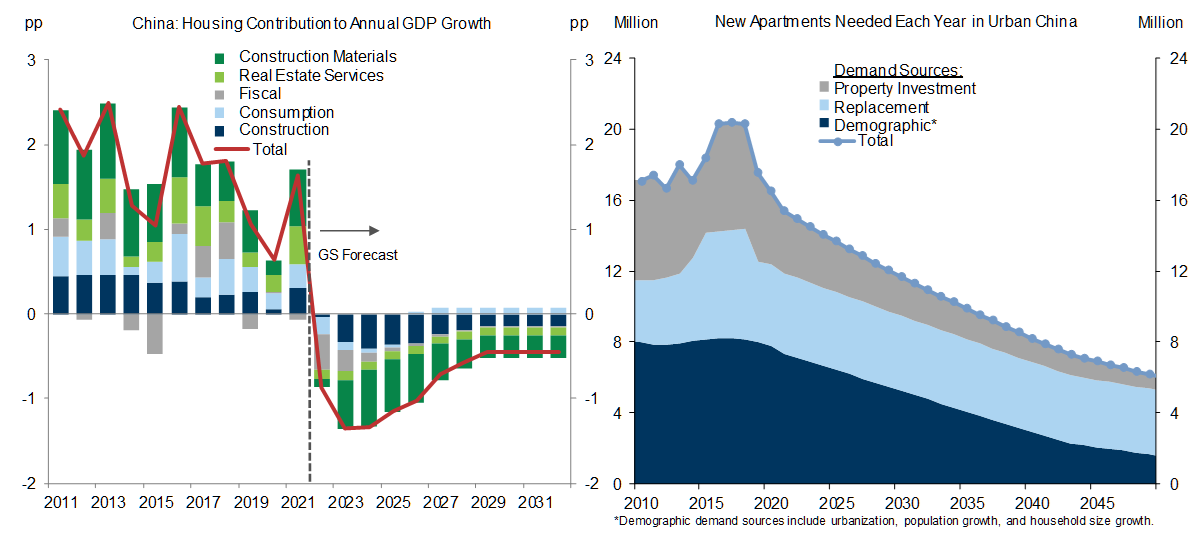

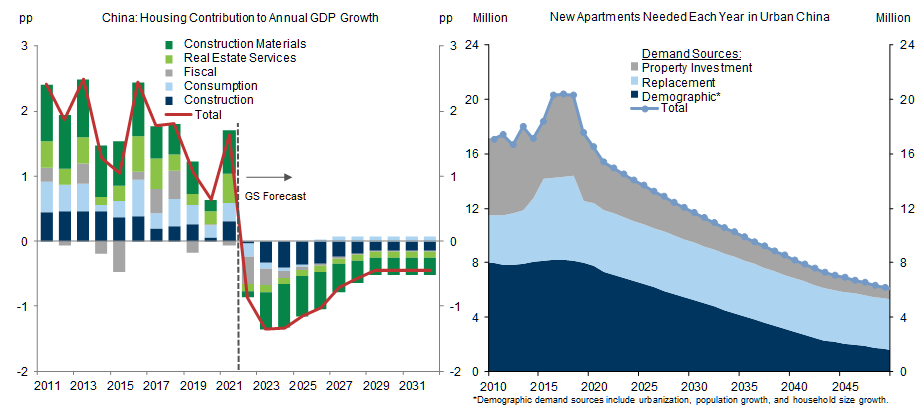

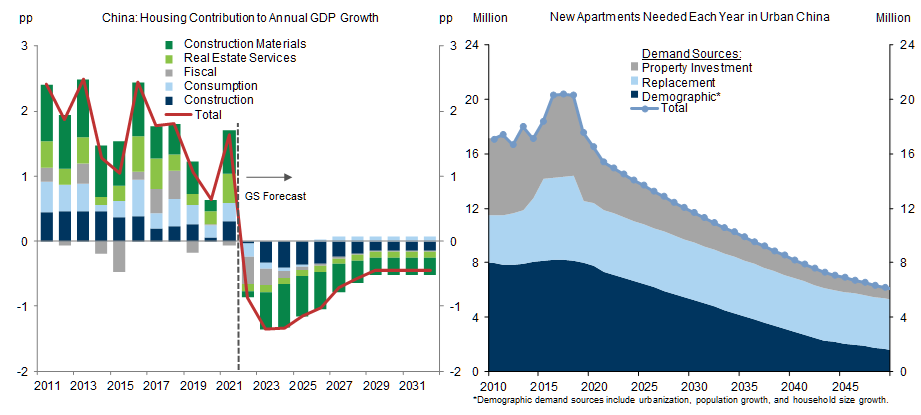

Our forecast of 4.8% growth in China next year is below consensus. The key driver of this muted outlook is a negative swing in the property sector growth impulse from an average of +1½pp in the last five pre-pandemic years to just above -1pp in 2022 and beyond. This reflects the negative impact of deleveraging on construction, consumption, government spending, real estate services, and construction materials activity (Exhibit 5, left panel).

In past cycles, Chinese policymakers would have reacted to such a slowdown via aggressive macro stimulus, but the policy reaction function appears to be changing. We expect policymakers to stem major downside risks, but with an intent to “do just enough”—implying a broadly stable policy rate and an increase in the annual augmented fiscal deficit by only 1pp next year. Policymakers appear to put a growing weight on objectives other than near-term GDP growth, including income distribution, financial stability, and decarbonization. Combined with the demographic headwinds[5], this shift lies behind our forecast of a large, but gradual and managed slowdown in trend GDP growth to around 3¼% by 2032.

Brazil is likely to underperform as well, with growth of just 0.8% in 2022, but the reasons are more short-term. Exhibit 6 shows that financial conditions have tightened very sharply, as the central bank has reacted to the large inflation overshoot with a series of dramatic rate hikes and as worrie

[Enter section heading here]

In recent months, we have also become more optimistic about the impact of fiscal policy on growth. This is straightforward in the Euro area, where the likely German center-left coalition looks set to spend more and the EU Recovery Fund will start funding investment projects in greater size next year.[3] But even in the US, the outlook is better than suggested by standard measures of the fiscal impulse.[4] The fact that the US personal saving rate remains at 7.5% as of September—a month with strong consumption and mostly without extended unemployment benefits—suggests that consumers have already largely absorbed the loss of government support without either a meaningful cutback in spending or an undue decline in the saving rate. Moreover, it suggests that the consumption boost from the $2.4trn stock in US pent-up savings is still ahead of us, at least in aggregate. Combined with the passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill on November 5—which we had assumed but which had been held up in intra-party Democratic wrangling—this has made us less concerned about a large negative US fiscal impulse than we were a few months ago.

Growth trends in the major emerging economies are likely to look more disparate, with relative weakness—both relative to consensus and to the long-term trend—in China and Brazil, but strong performance in India and Russia.

Our forecast of 4.8% growth in China next year is below consensus. The key driver of this muted outlook is a negative swing in the property sector growth impulse from an average of +1½pp in the last five pre-pandemic years to just above -1pp in 2022 and beyond. This reflects the negative impact of deleveraging on construction, consumption, government spending, real estate services, and construction materials activity (Exhibit 5, left panel).

[Enter section heading here]

In recent months, we have also become more optimistic about the impact of fiscal policy on growth. This is straightforward in the Euro area, where the likely German center-left coalition looks set to spend more and the EU Recovery Fund will start funding investment projects in greater size next year.[3] But even in the US, the outlook is better than suggested by standard measures of the fiscal impulse.[4] The fact that the US personal saving rate remains at 7.5% as of September—a month with strong consumption and mostly without extended unemployment benefits—suggests that consumers have already largely absorbed the loss of government support without either a meaningful cutback in spending or an undue decline in the saving rate. Moreover, it suggests that the consumption boost from the $2.4trn stock in US pent-up savings is still ahead of us, at least in aggregate. Combined with the passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill on November 5—which we had assumed but which had been held up in intra-party Democratic wrangling—this has made us less concerned about a large negative US fiscal impulse than we were a few months ago.

Growth trends in the major emerging economies are likely to look more disparate, with relative weakness—both relative to consensus and to the long-term trend—in China and Brazil, but strong performance in India and Russia.

Our forecast of 4.8% growth in China next year is below consensus. The key driver of this muted outlook is a negative swing in the property sector growth impulse from an average of +1½pp in the last five pre-pandemic years to just above -1pp in 2022 and beyond. This reflects the negative impact of deleveraging on construction, consumption, government spending, real estate services, and construction materials activity (Exhibit 5, left panel).

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.